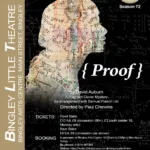

Season 72 Play 4 – Proof by David Auburn

Directed by

Cast

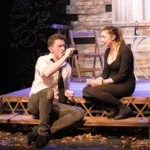

Catherine – Alice Smithson

Hal – Chris Avery

Claire – Anna Riley

Synopsis

Catherine, the twenty-something daughter of an esteemed mathematician, Robert, has laid him to rest. A devoted student, Hal, searching through his ex-professor’s papers, finds a pad of cutting-edge calculations. Catherine wrote the proof but how can she provide the evidence to support this?

This play won a basketful of awards in 2001 including the Tony Award for best play on Broadway. It is intriguing, with fascinating dialogue, well-developed characters and a twisting story line that tugs at your emotions and challenges preconceptions around sanity – and love.

Directors Notes

The word “proof” comes to us from an Indo-European root meaning “through” or “forward”. From this root comes one of the word’s primary English meanings: a test or trial in which a person or object is put through an ordeal, or placed in a forward position in the face of danger. Thus, we say of someone, “He has been proven in battle”, and we use phrases such as “bullet-proof” or “rust-proof”, or “the proof of the pudding is in the eating”.

A second sense of “proof” means the deployment of evidence or reasoning to establish a fact or validate theory. A “proof” in this sense is a demonstration that something is actually the case. The meaning of “proof” in Proof continually oscillates back and forth between these two senses, sometimes figuring as a test or ordeal – that is to say, an emotional trial – and at other times appearing as an exercise in logical demonstration.

In Proof, Auburn has found a witty, engrossing way to explore the notion of “proof” in several different senses – in the idea of a mathematical proof with its particular iron-clad inevitability, the notion of establishing the authorship of an intellectual work, and the daily proof that people seek to reassure themselves of the stability of reality and of their personal relationships.

The main character, Catherine, fears for her sanity, in part because her father was mad, and genetics is, after all, a powerful predictor of one’s own fate in life. But her fears are all the greater because she also shares her father’s genius. Her sister, Claire, who is intellectually undistinguished, has no worries about her mental health. And so we watch as a young woman struggles to be both brilliant, like her father, and normal, like her sister – to achieve the balance that our culture tells us may be impossible.

It has been a joy working with the cast and crew, as always at BLT. I give my thanks and congratulations for their professionalism, creativeness and sheer hard work.

I hope you enjoy the play.

Quotes from “Proof of What Happens When You Just Let Go” written by David Auburn for The Los Angeles Times in 2002

“Proof started with two ideas. One was about a pair of sisters: what if, after their father’s death, they discovered something valuable left behind in his papers? The other, more of a visual image than anything else, was about a young woman: I saw her sitting up alone, late at night, worried she might inherit her father’s mental illness.”

“Math was alien territory to me – had barely made it through freshman calculus in college – but I decided to set my story in Hardy’s world.”

‘Hardy was a Cambridge mathematician who wrote “A Mathematician’s Apology” – an attempt to explain the pleasures of doing math to a non-mathematical audience’.

“A mathematical proof became the “thing” the sisters find: my protagonist, Catherine, became convinced that she may have inherited her father’s talent – he was a legendary mathematician – as well as his illness. With these elements in place and feeling inspired by the meetings with the mathematicians I’d begun to have, I was able to finish a draft of the play.”

Paul Chewins